Rethinking BGP as Internet Diplomacy

BGP is more than a routing protocol—it’s the Internet’s diplomatic channel. Built on trust, not control, it enables global data flow. As policymakers focus on security and control, reframing BGP as a strategic, trust-based system is vital to preserving an open Internet.

TL;DR

This post re-frames the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP)—the little-known but essential system that routes global Internet traffic—as a form of digital diplomacy, built on trust, cooperation, and negotiation between autonomous networks. BGP reflects the Internet’s decentralized nature, functioning without central authority but vulnerable to misconfigurations, hijacks, or state interference.

Security-focused policymakers often view BGP through a national security lens, focusing on threats and control. This risks distorting its cooperative foundations and could lead to Internet fragmentation under the guise of digital sovereignty. Governments are increasingly using BGP to control or shut down connectivity during political unrest, raising concerns about censorship and isolation.

The post argues for public affairs professionals to bridge the gap between technical systems and policy, helping leaders understand BGP's strategic significance. By using diplomatic metaphors and accessible narratives, BGP can be framed as a tool of trust and global resilience, not just a technical protocol. If its story isn't told well, others may co-opt it to justify harmful, securitised policies.

Introduction

Cyber and telecom policy-makers across the world are often driven by urgent, high-stakes imperatives: protecting national sovereignty, defending critical infrastructure, minimising exposure to threats, and ensuring continuity in the face of disruption. Their instincts are shaped by national security paradigms — detecting threats, managing risks, and coordinating response mechanisms. When it comes to digital infrastructure, their default lens is one of control: the Internet is treated as a strategic asset — something to be secured, contained, and governed accordingly.

This perspective, while understandable, can sometimes distort how digital systems are interpreted. Take, for instance, the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) — a foundational yet largely invisible part of the global Internet routing system. BGP rarely features in public discourse, but it is absolutely critical to how data travels across the Internet. Every packet that moves from one corner of the world to another depends on BGP to determine which networks it must traverse to reach its destination.

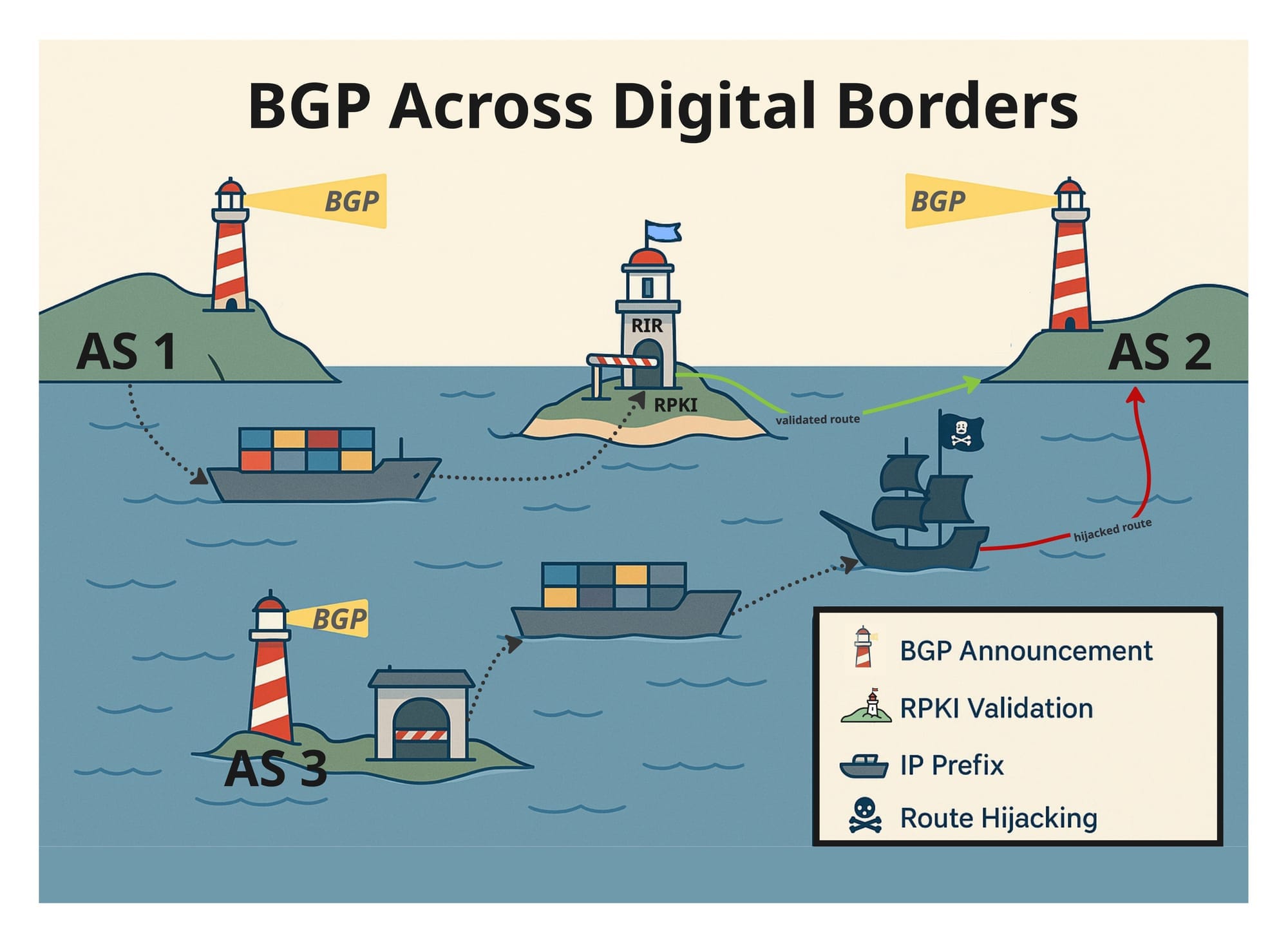

The Internet is a “network of networks” — thousands of independently operated entities known as Autonomous Systems (ASes), including Internet service providers, universities, corporations, and governments. These networks must constantly negotiate how data flows between them. BGP is the protocol that enables this negotiation. It operates through a decentralised system of routing announcements: “You can reach these IP addresses through me.” Routers across the Internet interpret these signals, apply local preferences, and determine the best available path forward.

But BGP was never designed with security as its core. It was built on trust, not enforcement. Networks are expected to announce only legitimate routes, but when that trust is broken — intentionally or otherwise — data can be misrouted, intercepted, or exposed. These incidents, known as route leaks or hijacks, have caught the attention of security-conscious regulators, who now view BGP less as a system of cooperative exchange and more as a vulnerability to national security.

Viewing BGP through a threat-based, securitised lens illustrates how technical systems can be misunderstood when seen only from a cyber-policy perspective. The protocol’s design reflects values like openness, cooperation, and voluntary coordination — principles that don’t always map neatly onto security frameworks grounded in control and enforcement. Still, how these systems are interpreted can shape entire regulatory agendas.

That’s why bridging the gap between technical design and policy perception demands adequate interpretive skills. Public affairs, when practiced as a strategic discipline, can help close the gap between technical systems and policy decisions.

Public affairs is not simply a support function or communications role. It is a discipline with its own distinct toolkit — combining policy analysis, stakeholder mapping, issue framing, diplomacy, and narrative design. Its role is not to simplify technical jargon in a one-way lecture, but to build shared understanding by framing complex systems, like BGP, in ways that are relevant. Through metaphors, context, and relatable storytelling, public affairs helps decision-makers grasp not just how things work, but why they matter. It is a form of applied pedagogy: shaping learning experiences, tailoring messages to diverse audiences, and guiding insight. And in a time when digital infrastructure is increasingly tied to geopolitical power, the way we frame technical issues can shape whether policies protect the open Internet — or unintentionally undermine it in pursuit of security.

One example of where public affairs can bring meaning to technical complexity is the Border Gateway Protocol itself. While often treated as a purely engineering concern, BGP can be interpreted as a window into the Internet’s geopolitical fabric. When framed through the lens of diplomacy, BGP can be more than just a routing protocol — it becomes a system of digital borders, trust relationships, and negotiated coexistence. It also might reveal how deeply this system is entangled with ideas of sovereignty and control.

Diplomacy Across Digital Borders

To understand BGP is to understand how digital borders are drawn, defended, and negotiated. It is a protocol built on trust, coordination, and the delicate balance of global cooperation — a language of Internet diplomacy. BGP governs how data moves between thousands of independently operated networks that form the Internet. Some of these networks are digital empires — global carriers and cloud giants. Others are smaller states — local ISPs, universities, and enterprises. Each is an Autonomous System (AS), managing its own domain with its own rules. But to reach destinations beyond their borders, they must exchange routes and traffic.

At its core, BGP facilitates this exchange. It doesn’t impose authority; it enables networks to announce, “Here are the destinations I can reach,” while listening to similar declarations from peers. There’s no central body verifying these claims. BGP functions by trusting that neighbours are truthful, routes are valid, and all participants are acting in good faith to keep the system running.

But just like in geopolitics, a single misstep can have global consequences. A false route, whether accidental or malicious can divert traffic, expose sensitive data, or cripple networks. To address these vulnerabilities, tools like Resource Public Key Infrastructure (RPKI) have emerged, enabling networks to verify who is authorised to announce what. Adoption is growing, but still uneven. RPKI introduces a layer of accountability into a system long sustained by informal norms and reputation.

The analogy with diplomacy runs deep. Networks, like sovereign states, don’t open their borders to just anyone. They set routing policies and filters — deciding which routes to accept, which paths to prioritise, and whom to trust. These decisions reflect technical goals, business interests, and evolving geopolitical dynamics. In many ways, they mirror visa policies or trade agreements.

Peering agreements resemble bilateral treaties: two networks agree to exchange traffic directly, without payment, for mutual benefit. Transit agreements are more hierarchical —smaller networks pay larger ones for broader access. It’s the toll paid for global reach. And when disputes arise — over misbehaviour, mistrust, or misalignment — the fallout can be swift: dropped connections, traffic misroutes, even surveillance risks. Like statecraft, resolution depends on negotiation and a shared interest in stability.

This diplomacy doesn’t play out in isolation. It flourishes in a constellation of multilateral forums — open, participatory spaces where norms are formed, cooperation is fostered, and shared infrastructure is stewarded. Institutions like the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) develop technical standards through open dialogue and rough consensus. Regional Internet Registries (RIRs) allocate resources based on transparent, community-driven policies. Network Operator Groups (NOGs) bring engineers and operators together across borders to share knowledge, build trust, and solve shared challenges. These are the Internet’s diplomatic institutions — voluntary, bottom-up, and peer-led.

BGP, then, is a case study in Internet diplomacy. It demonstrates how global interdependence can function without central authority — relying instead on coordination, transparency, and mutual accountability. Efforts like RPKI and the Mutually Agreed Norms for Routing Security (MANRS) initiative exemplify this ethos. They are not mandates but trust-based pacts — voluntary commitments sustained by peer pressure, reputation, and the shared understanding that the stability of the whole depends on the vigilance of each part.

Routing security is a global public good. Like climate stability or public health, it benefits everyone but requires everyone’s participation. One careless routing announcement, one misconfigured filter, can trigger instability that ripples far beyond the source. This is why cybersecurity, in the context of BGP, is not simply a matter of defense. It is a matter of diplomacy — of managing relationships, building trust, and upholding norms that maintain collective resilience.

Even the subtler aspects of BGP reflect the quiet diplomacy of international relations. Take "BGP communities" — metadata tags that influence how routes are handled downstream. They are the equivalent of backchannel instructions: “Advertise this route, but not to these regions,” or “Treat this path as less preferred.” These tags don’t enforce behaviour; they guide, suggest, and influence. It’s diplomacy in metadata form — nuanced, indirect, yet impactful.

The entire system operates on soft power. There are no binding laws — only expectations, best practices, and the constant recalibration of relationships. And yet, this informal architecture has proven remarkably resilient. The Internet continues to grow and adapt, even as political and commercial pressures mount. Its infrastructure remains largely cooperative, even in a geopolitical climate increasingly defined by fragmentation, surveillance, and digital sovereignty.

This is the paradox and the promise of BGP. Fragile yet resilient, anarchic yet coordinated, informal yet essential. It mirrors the real-world diplomacy of borders and alliances. And if we view BGP as a kind of digital border crossing, cybersecurity becomes something more than technical enforcement — it becomes a diplomatic act. Like all diplomacy, it begins with understanding, mutual respect, and a willingness to sit Around the Table.

For cybersecurity professionals and policymakers, this should be both a caution and a call. In BGP, we see a space where protocol and policy can converge. Here, RPKI becomes more than a technical validation system — it’s a passport regime. Filtering becomes a form of border policy. And participation in MANRS becomes a multilateral commitment to the integrity of the global commons.

BGP as a Tool for Digital Sovereignty

While the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) was originally designed to support the resilience and interoperability of the global Internet, it is increasingly being used as an instrument of digital sovereignty. Authorities seeking to assert control over the flow of information within and beyond their borders have adapted BGP to restrict, reroute, or entirely sever Internet connectivity—particularly during periods of political instability or unrest.

One of the most direct methods involves the withdrawal of BGP route advertisements. When network operators are instructed to remove advertised prefixes for domestic networks, those IP addresses effectively disappear from the global routing table, isolating national infrastructure from the rest of the Internet. Alternatively, operators may be ordered to stop announcing upstream routes, severing connections to external destinations. In some cases, “null” or blackhole routes are used, redirecting traffic to non-existent destinations. Governments may also direct providers to de-peer from Internet exchange points (IXPs) or upstream transit providers, fragmenting the country’s connectivity even further.

These tactics are often enabled by centralised control over international gateways and national telecommunications infrastructure. In such environments, a single authority can issue technical directives that result in widespread disconnection or rerouting within hours. The disruption is not limited to full blackouts; partial and targeted outages affecting specific services, regions, or platforms are also common.

In more advanced implementations, BGP controls are embedded within broader national strategies for network sovereignty. This may include the establishment of mandatory peering policies through state-run IXPs, strict filtering of BGP prefixes at border routers, and tight regulatory oversight of upstream providers. When paired with deep packet inspection (DPI), these measures allow for both broad disconnection and granular content filtering — enabling authorities to throttle, monitor, or block traffic based on keywords, protocols, or destination addresses.

Some network sovereignty frameworks take this even further by centralising all international BGP peering through a handful of state-controlled operators. In such models, only government-sanctioned networks are permitted to advertise or receive BGP routes across borders. Foreign prefixes are heavily filtered, and domestic routes are pruned to restrict access to banned or sensitive services. Routing-level control is then reinforced by DNS manipulation and DPI systems that monitor and shape traffic flows in real time.

These practices challenge the foundational notion of the Internet as a decentralised, open, and interoperable network. While sovereignty and national security concerns are real and valid, the increasing use of BGP as a control vector raises important questions about global connectivity, resilience, and flow of information.

Conclusion

There are high risks of BGP becoming a story of national security, because policy reactions can led to Internet fragmentation, which are the usual policy outcomes that are prescribed when policy makers want to defend digital sovereignty.

Risks associated with BGP — such as route hijacks and leaks—pose real threats. Whether accidental or malicious they can disrupt financial transactions, enable surveillance, or even take entire parts of the Internet offline. These are not hypothetical scenarios; they’ve already happened, with documented impacts on governments, businesses, and citizens.

Despite its significance, BGP continues to receive inadequate policy attention simply because we haven’t yet mastered how to tell its story. Policymakers easily fall into the narrative of increased dependence on digital infrastructure, making BGP a matter of national security, digital sovereignty, and where trust relies. Here is when BGP is used to enable digital sovereignty and Internet shutdowns.

As governments ramp up investments in cybersecurity and digital infrastructure protection, the window to shape the routing security narrative is now. Trusted networks, Internet governance, and cross-border data flows are increasingly part of the policy conversation. If we, as public affairs professionals and cyber policy advocates, don’t frame BGP in terms that resonate with decision-makers, others will — potentially with misinformed, oversimplified, or politically motivated frames.

Framing BGP as a strategic imperative, rather than a technical footnote, isn’t just helpful, it’s essential. This isn’t just about training. It’s about shaping the future of Internet policy, one narrative at a time.

P.S.

Numerous reputable sources document how governments regulate ISPs and mandate the deployment—and at times, manipulation—of BGP, DPI, and DNS to restrict access to specific services, enforce content controls, and monitor Internet activity. RIPE NCC Labs provides measurement-based investigations into BGP route hijacks and the impact of state policies on routing behavior. Citizen Lab conducts extensive research on censorship and surveillance mechanisms, including the use of DPI and DNS filtering by authoritarian regimes. Access Now tracks Internet shutdowns globally, highlighting cases where governments manipulate routing and DNS infrastructure. The Internet Society regularly publishes analyses on network disruptions and the broader implications of sovereign control over Internet infrastructure. The APNIC Blog offers deep technical insights into BGP behavior, Internet outages, and regulatory impacts in the Asia-Pacific region. Cloudflare and its Radar platform provide real-time and historical data on BGP withdrawals, DPI-based blocking, and global traffic anomalies. Oracle Internet Intelligence, formerly Dyn and Renesys, has analyzed worldwide BGP incidents and DNS failures during state-imposed outages. Kentik contributes detailed network-level analyses of regional and national Internet disruptions, including government-led shutdowns. NetBlocks monitors Internet accessibility in real time, identifying technical patterns consistent with DNS tampering and DPI interference. In particular, I was inspired by three sources: a report from LACNIC documenting the most significant BGP incidents, a detailed article examining the state of BGP in China, and Dr. Anthony J. Pennings high-level briefing on the evolving intersection of routing policy and digital sovereignty.